How to Add Custom Fonts to Your Blogger or WordPress Blog

Published by Drew Hendricks • Resources • Posted October 4, 2018 ContentPowered.com

ContentPowered.com

If you’ve been playing around with web design on a casual basis, or if you’re looking to add a little variety to your site, you might feel that one of the best ways to do so is with fonts. Playing around with fonts can be pretty fun and satisfying, but there’s one major roadblock with typefaces on the web.

We’re used to seeing all kinds of different fonts all over the web, but when you think about it, you almost always see those fonts in images. The actual text of a webpage is one of the standard fonts, like Verdana, Times New Roman, or Arial. Why don’t bloggers spice up their blogs with new fonts?

The answer lies in the way fonts work. Fonts are files installed on a computer, as part of the operating system most frequently. You can use any font you want in your web design, but it will only be visible to anyone who has the font installed on their computer. It will look fine for you, of course, but when you view the site from your phone, from another computer in your network, or a user’s computer half the world away, it won’t have that font installed. Your text will display as one of the default fallback fonts, and the user will never know you tried to use a different font in the first place. The only hint might be if there’s odd spacing because the font you wanted to use is wildly different than a standard font.

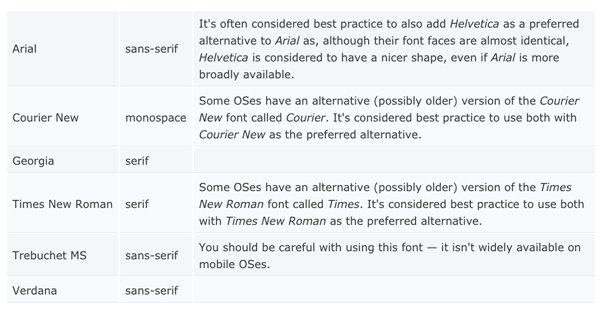

The few fonts available to virtually every user, by the way, are called the “web safe fonts.” These are fonts that are available on pretty much every device by default, and thus are safe to use for the majority of your potential traffic. You can see a list of these fonts and an overview of how it all works here. Arial, Courier New, Times New Roman, and Verdana are common web safe fonts.

Throughout the years, there have been a few workarounds to get fonts to display. Some old websites would use scripts that tried to get the user to download a font to use to display the site correctly, but this is incredibly dangerous. No intelligent modern user will trust such an automatic download and install, and indeed, this method was used to hide all manner of malware.

Enter: Web Fonts

At this point, enough people had enough organization to make broad decisions about the way the web would work moving forward. This is how we end up with modern standards like CSS and which elements of HTML are supported and which aren’t. This is also how we ended up with web fonts.

Web fonts are fonts that are downloaded as part of a server call-and-response when a user loads a page with a non-standard font. Web fonts had to be created using a special tool back then (in 1997) and so the idea didn’t catch on. Then, in 2010, the Mozilla Foundation, Microsoft, and Opera banded together to get the W3C to support the WOFF format. WOFF, or Web Open Font Format, supports a number of fonts and works in that same old method, simply downloading and using the font in the background. However, because it’s a limited and verifiable format, it’s not exploitable by malware.

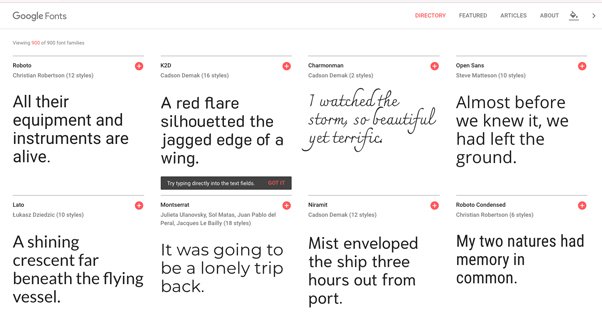

Also in 2010, Google launched Google Fonts, which is a database of free web fonts web designers are able to use. Some of these fonts are unique, while others mimic existing non-web fonts. As of this writing, Google Fonts has some 889 fonts in their list.

If you want to use a non-standard font with your web design, it’s fairly easy. All you really need to do is use a designated web font. How can you do that? Let’s check it out.

Where to Find Fonts

Before we begin, there’s one important note to make. There are nearly 900 available fonts in the Google Fonts directory, but you might want something different. In fact, you can use pretty much any font as a web font with the right formatting. The thing is, most fonts are not actually free to use. Many fonts might have a license that requires you to pay to use the font, or to use it only in noncommercial ways, or to credit the creator of the font. As you might expect, this can be a hassle – and can be expensive – so I’m mostly going to ignore it entirely. Use a freely available font and save yourself the hassle.

If you don’t like the offerings available through Google Fonts, there are innumerable font directories of all kinds available. Here are some options:

- Free font distributors: Font Squirrel, DaFont, Everything Fonts

- Paid font distributors: Fonts.com, MyFonts, or font manufacturers like Linotype

- Online font services: Google Fonts, typekit, Cloud Typography

Online font services are in some ways worse than buying fonts directly. Google Fonts is free, but other font services are usually subscription-based, and the costs can add up over time.

Installing and Using a Font

Alright, for the instructions I’m giving you, I’m assuming you can find something you want to use within the Google Fonts library. Speaking of:

Step 1: Find a font you like. Google Fonts is a pretty robust system. You can dynamically change the text, text size, formatting, and even font style within the style library. For examble, Cedarville Cursive only has one style, while Titillium Web has 11 styles, including bolds, italics, extra light, and extra heavy character weight.

In addition, you can filter through fonts looking for specific characteristics you want for your web design. You can search for serif or sans serif fonts, display fonts, handwriting-style fonts, and monospace fonts. You can look for fonts that are trending, and you can search for different levels of thickness, style availability, font slant, and character width. You can even adjust the background color of the Google Fonts page, to see how a font might look in a different color.

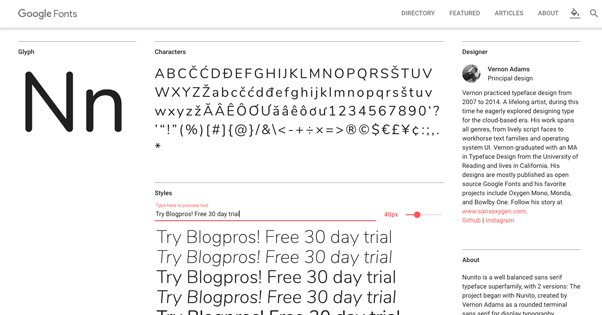

Let’s say you want to use, say, Nunito. On the font page, you can see a lot of different information, including a character list, information about the designer of the font and the font itself, a display of the available styles, geographic distribution for the font’s use, and the number of times the font has been used in the past week.

Step 2: Use the font. Up at the top of the font page, you can see a “select this font” button. Click that, and a little bar will appear at the bottom of the screen. This is Google’s font widget. You can go back and choose other fonts to use as well, or just stick with the one font.

Why might you want more than one font? Some designers like to use different fonts for headlines. You might want a handwriting-style font for quotes. You can use different fonts for block quotes or image captions. Really, it all comes down to how much you want to deal with configuring your font usage.

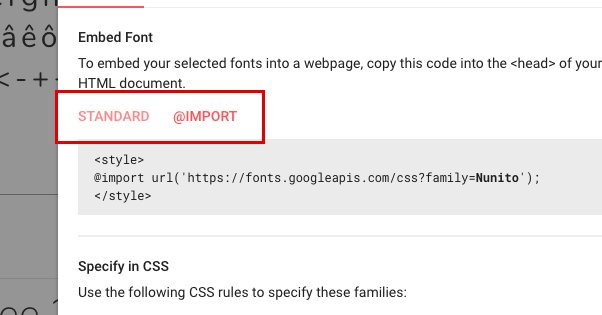

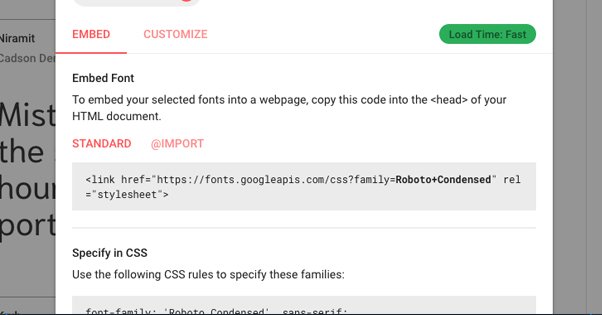

If you click the bar at the bottom, you can see the expanded Google widget for fonts. It will show you the fonts you have selected, and gives you two options: embedding the font as-is, or customizing it. To embed the font as is, look below where you see Standard or @Import.

There’s a very deep technical set of differences between Standard font imports and the @import option. Frankly, none of it really matters to someone who is reading this basic blog post about using new fonts. Don’t choose @import, just use the standard import option.

If you click the “customize” option, you can see different options usable with your specific font choice. Our Nunito choice is available in 14 different styles ranging from extra light to extra dark, with a regular and a bold option default available. You may want to add italics and bold italics if you want to use those formatting options in your text. You can also see that Nunito works with the Latin alphabet set, the extended Latin set, and the Vietnamese set. You probably only need Latin, but you can choose Latin Extended if you want extra character support.

You will note in the upper corner that there’s a green oval with “load time: fast” in it. This is Google’s estimate of how quickly this particular font will load for a user. Essentially, the more fonts you want to use and the more styles of a given font you want to use, the longer it will take for them to load for the user, and the longer page load times will be.

This is relevant primarily for SEO. Page load times are a search ranking factor, so throwing 20 different fonts onto a pile just for a few odd formatting options might hurt more than it helps. You don’t want to slow down your site just to load a font you only use for two quote boxes in your page.

Step 3: Paste the code. Once you have the configuration options chosen and the fonts you want to embed, look in the box for Standard. You’ll see something that looks like <link href=https://fonts.googleapis.com/css?family=Nunito:400,700 rel=”stylesheet”>.

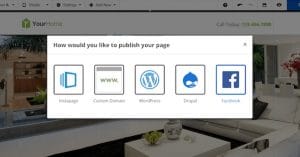

This is your font embed code. In a standard website, you would paste this into the <head> section of your code. However, if you’re using Blogger or WordPress, you’ll need to take a slightly different set of actions.

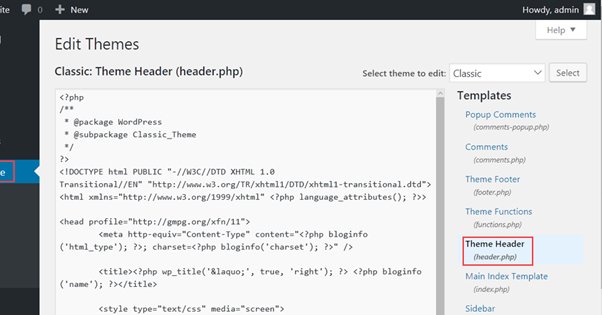

WordPress

For WordPress sites, find your html template file for your theme. It’s generally a good idea to create a child theme for your parent theme, so you’re not making edits you can’t roll back. Some themes prevent editing the original theme as well. Different themes are laid out in different ways, but you generally want to find your header.php file to edit. Find the <head> section and add in your font code.

If you’re concerned about site speed and are thus using the Genesis framework, you’ll need to edit through Genesis. Go to your Genesis dashboard and find Theme Settings. In the Header and Footer Scripts section, paste in the code.

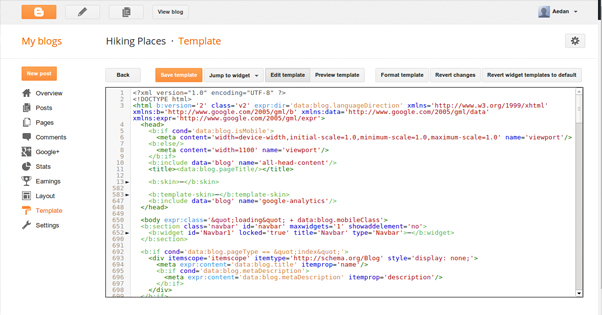

Blogger

For blogger, you will need to go to your Blogger dashboard and click on the Template section. There, click Edit HTML, and find the <head> section of your code.

You may need to edit the code block you paste in to use with Blogger. If your font doesn’t work properly, go back in and find your code block. The part where it has rel=”stylesheet”>, add in a /, so it looks like rel=”stylesheet”/>. If the stylesheet bit is not the last bit, put the / at the end before the >. That’s the important part, the position of the /.

Now, in order to actually use the font, you need to call for it in your CSS. You’ll need to use font-family: ‘Nunito’, or whatever font family you’ve actually chosen, to specify that font as the one to use for your text.

Now all that’s left is to save your changes and use your fonts in your designs. You can always change your fonts later, or add new fonts to your code. Just remember that if you remove a font family, any code that currently calls for that font family will fail and fall back to a default web safe font. Make sure you’re no longer using a font before you remove it from your code.